Crime and New Orleans

Categories

Crime and New Orleans

People

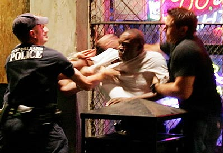

from New Orleans were not surprised to see video of police beating a

64-year-old man in the French Quarter. The only surprise is the

increased attention the incident received due to the continued media

focus on New Orleans, although news reports I saw took pains to point

out the "high levels of stress" New Orleans police are under.

People

from New Orleans were not surprised to see video of police beating a

64-year-old man in the French Quarter. The only surprise is the

increased attention the incident received due to the continued media

focus on New Orleans, although news reports I saw took pains to point

out the "high levels of stress" New Orleans police are under.

Despite the attempts to explain away the officer's behavior, the incident fits into a well-defined pattern of police conduct in New Orleans. In the last year, seven young black men have been killed by New Orleans police, and none of the officers involved have been punished.

This year has seen mounting evidence of a police department out of control. Less than a week before Hurricane Katrina, on Wednesday August 24, Keith Griffin, a New Orleans police officer, was booked with aggravated rape and kidnapping. According to a Times-Picayune report, "Griffin is accused of pulling over a bicyclist under the guise of a police stop in the early morning hours of July 11. The two-year veteran officer allegedly detained the woman, drove her to a remote spot along the Industrial Canal near Deslonde Street, then sexually assaulted her."

This is hardly an isolated incident. Another recent Times-Picayune article reported, "in April, seven-year veteran officer Corey Johnson was booked with aggravated rape for allegedly forcing a woman to perform oral sex, after he identified himself as an officer in order to enter the woman's Treme home."

Another article states "Eight officers were arrested during a six-month stretch last year on charges that ranged from shoplifting to theft to conspiracy to rob a bank...In April 2004, 16-year veteran James Adams was booked with aggravated kidnapping, extortion and malfeasance after he was accused of threatening to arrest a woman unless she agreed to have sex with him. "

Police misconduct in this notoriously corrupt city goes back decades, and occasionally it explodes in scandal. In a September 2000 report, the progressive policy institute reported "a 1994 crackdown on police corruption led to 200 dismissals and upwards of 60 criminal charges, including two murder convictions of police officers. Investigators at the time discovered that for six months in 1994, as many as 29 New Orleans police officers protected a cocaine supply warehouse containing 286 pounds of cocaine. The FBI indicted ten officers who had been paid nearly $100,000 by undercover agents. The investigation ended abruptly after one officer successfully orchestrated the execution of a witness."

According to one community activist I recently spoke with who is familiar with the investigations, "That crackdown just scratched the surface. They didn't even really begin to address the problems in the New Orleans police."

According to a 1998 report from human rights watch "Former Officer Len Davis, reportedly known in the Desire housing project as 'Robocop,' ordered the October 13, 1994 murder of Kim Groves, after he learned she had filed a brutality complaint against him. Federal agents had Davis under surveillance for alleged drug-dealing and recorded Davis ordering the killing, apparently without realizing what they had heard until it was too late. Davis mumbled to himself about the '30' he would be taking care of (the police code for homicide) and, in communicating with the killer, described Groves's standing on the street and demanded he "get that whore!" Afterward, he confirmed the slaying by saying 'N.A.T.' police jargon for 'necessary action taken.' Community activists reported a chilling effect on potential witnesses or victims of brutality considering coming forward to complain following Groves's murder."

The white-flight suburbs around New Orleans are in many ways worse. During the 1980s, Jefferson Parish sheriff Harry Lee famously ordered special scrutiny for any black people traveling in white sections of the parish. "It's obvious," Lee said, "that two young blacks driving a rinky-dink car in a predominantly white neighborhood? They'll be stopped."

The New Orleans Gambit newspaper reported that 1994, "after two black men died in the Jefferson Parish Correctional Center within one week, Lee faced protests from the black community and responded by withdrawing his officers from a predominantly black neighborhood. 'To hell with them,' he'd said. 'I haven't heard one word of support from one black person.'"

The Gambit also reported in April of this year that in Jefferson Parish officers were found to be using as target practice what critics referred to as "a blatantly racist caricature" of a Black male. Sheriff Lee laughed when presented with the charges. "I'm looking at this thing that people say is offensive," he says. "I've looked at it, I don't find it offensive, and I have no interest in correcting it."

These accusations of "target practice" gained force a few weeks later with the May 31 killing of 16-year-old Antoine Colbert, who was behind the wheel of a stolen pickup truck with two other teens. 110 shots were fired into the truck, killing Colbert and injuring his passengers. In response to criticism from Black ministers over the incident, Lee responded, "they can kiss my ass."

As has been widely reported, the town of Gretna, across the Mississippi from New Orleans and part of Jefferson Parish, stationed officers on the bridge leading out of New Orleans blocking the main escape route for the tens of thousands suffering in the Superdome, Convention Center, and throughout the city.

As the LA Times reported on September 16, "little over a week after this mostly white suburb became a symbol of callousness for using armed officers to seal one of the last escape routes from New Orleans - trapping thousands of mostly black evacuees in the flooded city - the Gretna City Council passed a resolution supporting the police chief's move. 'This wasn't just one man's decision,' Mayor Ronnie C. Harris said Thursday. 'The whole community backs it.'"

Arguably, the actions of the Gretna police were one of the biggest dangers to public safety to arise from this tragedy, perhaps second only to the criminally neglected levees. Anyone that wants to focus on relief for the "victims" needs to focus on what exactly people from New Orleans are victims of: racism, corruption, deindustrialization, disinvestment, and neglect. That is why agencies and organizations such as Red Cross, FEMA, Scientologists, their hundreds of well-meaning volunteers are not really providing relief - they aren't addressing the nature of the problem.

We call hurricanes and earthquakes "natural disasters," but the contours of these disasters are manmade. As recent earthquake and hurricane-related mass deaths in South Asia and Central America demonstrate, who lives and who dies is intricately related to issues of poverty and access. Whether the homes are built in safe areas, the soundness of the structures, the length of time it takes for relief to arrive, all of these are intricately tied to poverty. And yet the media generally ignores these issues, and repeats the message that "nature doesn't discriminate." Because of this message, relief is misdirected, and when those receiving the relief aren't sufficiently grateful, the givers become resentful.

An article in this Sunday's New York Times reports on a community of displaced New Orleans residents in rural Oklahoma, where local residents are "glad to see them go." "With each passing day," the Times reported, they "could feel the sympathy draining away." The problem is the perception that this is a problem that could be fixed by a place to stay in another state, some hand-me-down clothes, and a few meals. For many of us from New Orleans, what hurts the most is the loss of our community, and charity doesn't help to heal those wounds at all. Mayaba Benu, a community activist currently in the city, told me "I miss everyone. There's a lot of reporters here, a lot of contractors and FEMA folks, but not many people from New Orleans."

While thousands of out-of-state contractors line-up for work, including hundreds of trash hauling trucks from around the US lined up near City Park, the people of New Orleans are still being excluded from opportunities to take part in the reconstruction of their city. In fact, it seems to many that out-of-state workers are more welcomed than the New Orleans diaspora.

Jenka Soderberg, an indymedia reporter and volunteer at the Common Ground Collective reports from her experience at a New Orleans FEMA compound, "I went to the FEMA base camp for the city of New Orleans. It made me feel sick to my stomach. We walked around this absolutely surreal scene of hundreds of enormous air-conditioned tents, each one with the potential of housing 250 people -- whole city blocks of trailers with hot showers, huge banks of laundry machines, portajohns lined up 50 at a time, a big recreation tent, air-conditioned, with a big-screen tv, all of it for contractors and FEMA workers, none of it for the people of new orleans."

Inside the FEMA camp, she was told by contractors, "the tents are pretty empty, not many people staying here." However, "we don't combine with the evacuees -- we have our camp here, as workers, and they have their camps."

Soderberg comments, "thousands of New Orleans citizens could live there while they rebuilt and cleaned their homes in the city. But instead, due to the arrogance of a government bureaucracy that insists they are separate from the 'evacuees', and cannot possibly see themselves mixing with them and working side by side on the cleanup, these people are left homeless, like the poor man I talked to earlier in the day, living under a tarp with his mother buried under the mud of their house. Why can't he live in their tents? It makes me so sad and mad to see so much desperate need, and then just blocks away to see this huge abundance of resources not being used. I have seen no FEMA center that is actually providing any aid for people -- I have been to this main FEMA base camp and three others in New Orleans, and each of them have signs saying 'No public services available at this site/Authorized personnel only'"

And with poor people out of the city, the developers and corporations are grabbing what they can - but there are no shoot-to-kill orders on these well-dressed looters. NPR and other media have portrayed developer Pres Kabacoff as a liberal visionary out to create a Paris on the Mississippi. The truth is that Kabacoff represents the worst of New Orleans' local disaster profiteers. It is Kabacoff who, in 2001, famously demolished affordable housing in the St Thomas projects in New Orleans' Lower Garden District and replaced it luxury condos and a Wal Mart. "New Orleans has never recovered from what Kabacoff did," one housing activist told me. "It was a classic bait and switch. He told the city he was going to revitalize the area, and ended up changing the rules in the middle of the game and holding the city for ransom. He made a ton of money, the rich got more housing, and the poor got dispersed around the city."

This year, Kabacoff has had his eyes on razing the Iberville housing projects, a site of low-income housing near the French Quarter. While Iberville residents were in their homes, they were able to fight Kabacoff's plans, and held numerous protests. Now that they are gone, their homes (which were not flooded) are in serious danger from Kabacoff and other developers seeking to take advantage of this tragedy to "remake the city."

The people of New Orleans need a voice in this reconstruction. But what would community-controlled reconstruction look like? Organizers are starting to grapple with these issues.

Dan Etheridge works with the Center for Bioenvironmental Research at Tulane and Xavier Universities. He is currently organizing to create collaborations and build partnerships between community organizations and planning professionals "not because its benevolent but because we will have a better city if the community has a say in its reconstruction."

He has organized an upcoming conference at Tulane University to bring together planners, architects, structural mitigation experts, geographers and other experts, along with grassroots community leaders from New Orleans, people such as "the social aid and pleasure clubs, Mardi Gras Indian representatives, ACORN, building unions, artists, teachers, public housing resident councils, Peoples Hurricane Fund representatives," and other community voices.

He hopes this will be "the starting point for an ongoing program, a networking and organizing opportunity for autonomous public projects. We want our vision to be part of the master plan for rebuilding the city, but we want community groups to have access to the skills and funding they need for smaller projects towards reestablishing the complicated fabric of the city. Instead of falling through the cracks, we want projects to grow up through the cracks."

In a press conference today outside Orleans Parish Prison Critical Resistance New Orleans organizer Tamika Middleton said, "Katrina's aftermath reflects the way we as a nation increasingly deal with social ills: police and imprison primarily poor Black communities for 'crimes' that are reflections of poverty and desperation. Locking people up in this crisis is cruel mismanagement of city resources and counters the outpouring of the world's support and concern for all survivors of Hurricane Katrina."

Middleton is part of a coalition demanding an independent investigation into the evacuation of OPP and amnesty for those arrested for trying to feed and clothe themselves post-Katrina, while calling for real public safety in a rebuilt New Orleans. "Rising from the devastation of Katrina, we have an amazing opportunity to rebuild a truly new and genuine system of public safety for New Orleans," said Xochitl Bervera, Co-Director of Families and Friends of Louisiana's Incarcerated Children.

Discussing FEMA and other official "relief" agencies, Jenka Soderberg says, "its so different from how we are working at the common ground collective, or at Mama Dee's in the city, or the other community places that people are starting up -- where neighbors are helping neighbors, people just helping each other. It's so different when we are all human together, instead of a militarized, razor-wired, fenced-in compound like the FEMA camp that keeps out the people in need and keeps the contractors and workers inside."